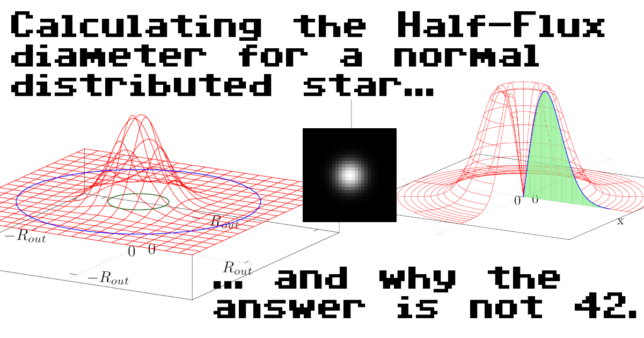

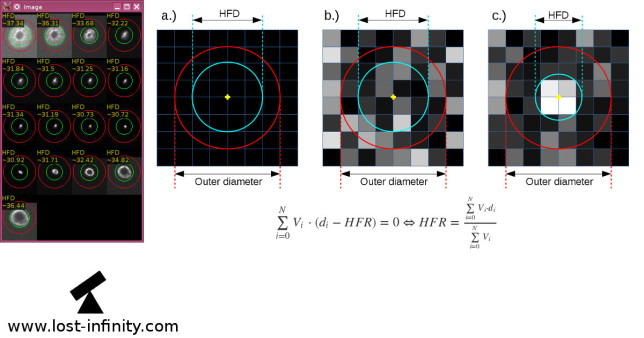

Calculating the Half Flux Diameter for a perfectly normal distributed star…

… and why the answer is not 42.

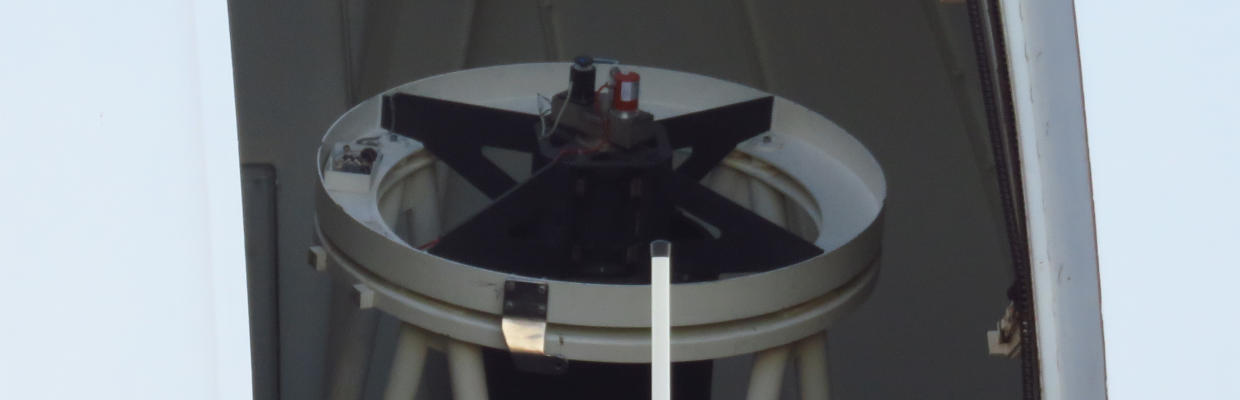

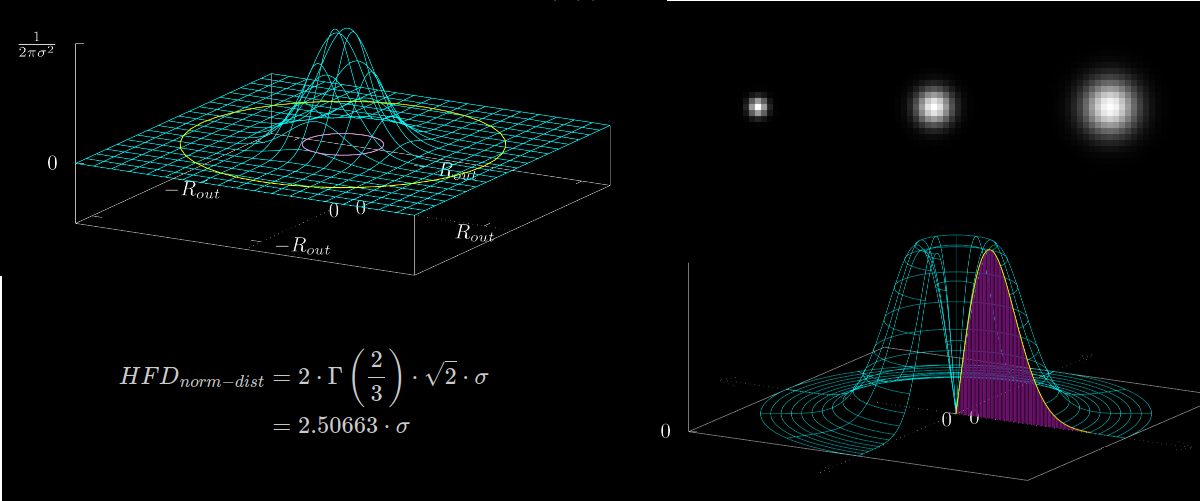

The goal of this article is to “manually” calculate the Half Flux Diameter (HFD) for a perfectly normal distributed star. Initially, I decided to add perfectly normal distributed stars with different σ values as additional unit tests to my focus finder software project. A few of those star images with σ=1, 2 and 3 are illustrated in figure 1.

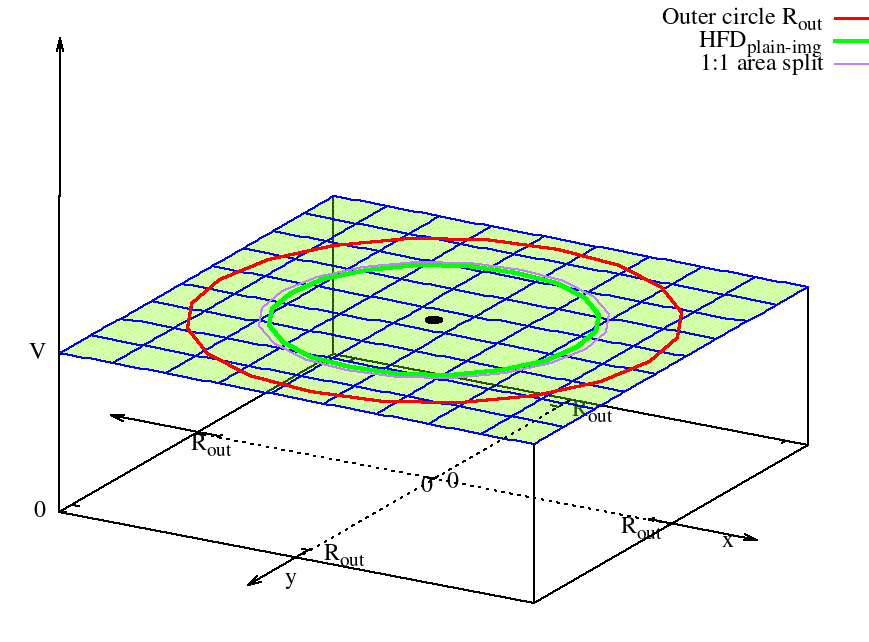

Previously, I examined the Half Flux diameter (HFD) for a plain image. In that article I cover some aspects in greater detail which I am reusing in this article. If something is unclear I recommend to read this article first.

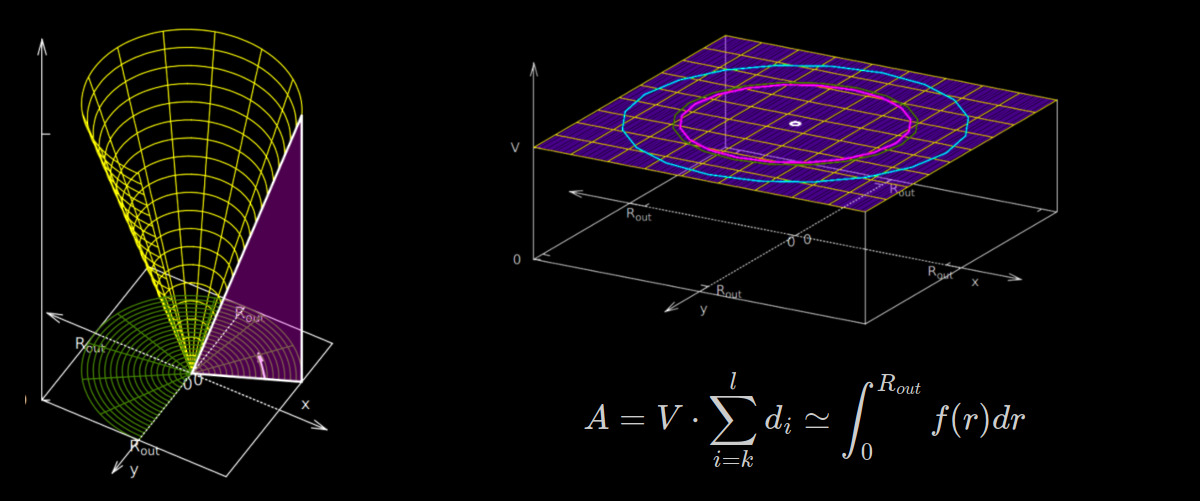

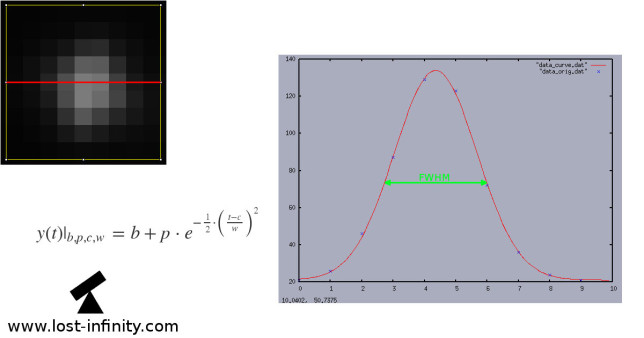

A 2D image can be represented in the 3D space where the $x$- and $y$-axis are used to express the position of the pixel and the $z$-axis to visualize the intensity (pixel value) – see figure 2 below.

Following a similar approach like for the plain image, the Half Flux Diameter (HFD) for such an image will be derived in the following sections.

Quick summary

For those who just seek for the facts – here is a quick summary:

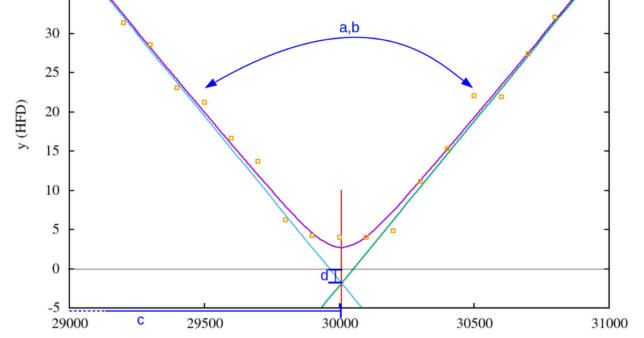

- The Half Flux Diameter ($HFD$) for a perfectly normal distributed star is $HFD_{norm-dist} = 2 \cdot \Gamma\left(\frac{2}{3}\right) \cdot \sqrt{2} \cdot \sigma = 2.50663 \cdot \sigma$ where $\sigma$ is the variance of the distribution.

- The result does not depend on $R_{out}$ and also not on the normalization factor of the distribution.

- The expression was derived by converting the $HFD$ formula into an integral and inserting the normal distribution function as intensity (pixel value). The integral was solved by using a relation between the normal distribution and the $\Gamma$-function.

- For the volume integration the second Pappus–Guldinus theorem is used.